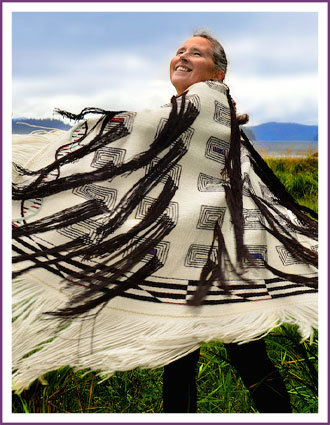

TERI May (Laws) ROFKAR

Chaas’ Koowu Tia’a

• Tlingit Culture

Inducted: 2017

Deceased: 2016

TERI May (Laws) ROFKAR

Chaas’ Koowu Tia’a

Teri Rofkar, a Raven from the Snail House, was a renowned Tlingit artist, a weaver know nationally and internationally for her spruce tree root baskets and Ravenstail robes. She explored and mastered the gathering and Ravenstail weaving technique of twining used in the 6,000 year-old Tlingit traditional culture. Then, throughout her thirty-year career as an artist Rofkar generously shared this traditional knowledge by leading workshops, teaching and giving demonstrations and, of course, through the examples of the baskets and Ravenstail robes she created.

Born in California, she moved to Anchorage as a young child, graduated from Dimond High School in 1974, was married in October 1974 and arrived in Sitka, Alaska, in 1976. She grew up in a household where both parents were artists. In the summers Rofkar visited her maternal grandmother in the village of Pelican, Alaska who introduced her to traditional Tlingit weaving and gathering techniques at an early age.

Her Ravenstail robes and spruce root baskets are in the collections of museums throughout the country. She received many distinguished awards for her art, such as the NEA Heritage Fellowship Award for Traditional Arts in 2009 (the nation’s highest award for traditional folk arts and crafts), the Rasmuson Foundation Distinguished Artist Award in 2013 and an Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts from the University of Alaska Southeast in 2015.

The more Rofkar practiced her art utilizing the traditional techniques, the more she gained insight into Tlingit culture and its connections between the present and the past, the culture and the natural world, science and math. As an individual, she cared deeply about how to live, and create, responsibly in today’s world.

View Extended Bio