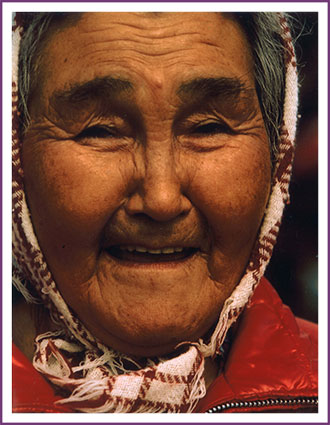

ANNIE Aghnaqa (Akeya) Jackson ALOWA

• Leadership

• Education

• Healer

Inducted: 2016

Deceased: 1999

ANNIE Aghnaqa (Akeya) Jackson ALOWA

During her lifetime, Alowa served as a midwife, community health aide, and advocate for health and justice. During 1955-1956 Alowa became a midwife, tending women in childbirth. Shortly thereafter, she became a community health aide, receiving training at the Kotzebue Hospital. Communication was very limited between mainland Alaska and Savoonga, on Saint Lawrence Island. The only radio available was at the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ school and communications could only occur at scheduled times. Therefore, life and death health issues were handled locally by innovative community health aides.

Alowa moved to Northeast Cape and lived there from 1963 to 1970 working as a community health aide, for which she received no compensation, and maintaining a paying job at the U.S. Air Force base. During that time, she began to notice serious health problems among island residents – including members of her own family. She began to see cancer, low birth weights, and miscarriages among her people.

When the military vacated Northeast Cape in 1972, Alowa saw they had left a huge amount of hazardous material in landfills, including massive amounts of oil and fuel products, paint, batteries, and metal garbage. Buildings were left intact. Later, she learned of hazardous materials buried at the site, including asbestos, PCBs, pesticides, solvents, lead-based paint, fuel tanks, and barrels full of lubricants and fuel. She became concerned these hazardous materials posed a long-term health risk for island residents and began to address these concerns with the Alaska delegation in Washington, D.C., with state and federal agencies, and with the military to ensure responsible cleanup. As a result, there was a massive cleanup of Northeast Cape and all material was removed. Alowa served on the board of the Norton Sound Health Corporation. She later developed cancer and continued her tireless work for the health and justice of her people until her death in 1999.

View Extended Bio